Authors note: Wrote this at the beginning of the pandemic. Recently re-edited slightly. I initially thought of changing the narrative arc, creating more drama, a drastic ‘change’ in the narrator, a great sense of perseverance, perhaps. But in the end, after re-reading, I came to the conclusion that the story is what it is about — the slow and subtle emotional death of a man, which is more common than we might think, more typical than we’d like to allow ourselves to believe. Sometimes people give into apathy, ennui swallows us whole. Entropy exists. Tragic, whatever.

There is, of course, the concept of somebody achieving harmony with nature, a coalescence with the world around them. A pandemic plus technology makes that very difficult, if not impossible. One can only hope. And here’s another thing that’s maybe true: when you’re emotionally dead, life is easier. Easier, not better.

Another small thing — I don’t like this piece. It’s overwritten and wearisome. The narrator annoys me. I cringe at many of the paragraphs and wish I’d never written them. So why release it? Because it’s finished, the ending is fun, and sometimes people like what I don’t like.

On to the next one. Enjoy for now!

Invisible Enemies by Gordon Glasgow

We had just moved to Prenzlauer Berg, an upper-middle-class area in East Berlin that’s home to a healthy mix of young families and artists, old Germans and Soviets who had been there since the 40s, 50s, and 60s, not planning on leaving any time soon. Like most of Berlin, from what I remember, the streets in Prenzlauer Berg were tree-lined and broad, chestnut, oak, maple, and pines hanging over a relatively clean pavement, a width one could confuse with an airport tarmac. These streets were large, and when spring arrived the trees were a sprightly green that coalesced beautifully with leftover foliage from seasons past. Expenses were cheap, it was a compulsively livable place. Many landed in Berlin to get away from everywhere else.

The city had a joie de vivre one could rarely find in any urban metropole. Bars and clubs open through the night. Everyone smoked cigarettes yet lived longer than Americans. Galleries were full and the city brimmed with artists and graduate students, refugees and writers, ‘misfits’ and ‘outcasts,’ and the elderly and the young and in general all those who took their time and en- joyed being alive. It wasn’t perfect and there was crime and a general bohemian ennui, but it was still a time capsule within an ever-changing world. Industry was encroaching but communities were resilient, unwilling to give in to hikes in prices and declines in lifestyle, averse to backing down the way every other place seemed to do.

I liked it there, so did Agnes.

Agnes and I met on a fellowship for journalism, hers sponsored by the United Kingdom, mine by the United States, her focus politics and mine culture, not that the two are mutually exclusive. I liked how her name represented an aspect of the old world, a valuable embodiment of something genuine that I’ve always pined for. Not many people were named Agnes anymore. When I first heard the name it put forth an acerbic, off-putting taste in my mouth, a taste that was dissociated from her beauty and grace. It was one of the many things about Agnes that I gravitated toward.

We got along off the bat and spent most of our time wasting time, doing not much at all, watching stupid videos on the internet at each other’s apartments, going on walks at rare times of day when the streets were most quiet, buying odd, often neglected and overlooked items off of supermarket shelves and trying to make a unique dish out of them. Going out with colleagues and friends and drinking too much and not having to go home and spend the night alone afterward. Enduring a hangover in each other’s arms. Losing and gaining time in the oddest of ways, you know, the eerie and particular activities that people tend to engage in while falling in love. We took a bus to Poland under the guise of buying cheaper cigarettes but I think we really went because we just wanted to sit on a long bus ride together and eat candy and look out the window while being the couple that are happy to not have to sit next to a stranger. We would stand in front of mirrors together and openly discuss how our reflections changed over time. We each agreed that from one moment to the next, our own faces would be familiar and then immediately become unfamiliar, all within a matter of seconds. There you are, there you aren’t.

These seemingly banal feelings were valuable and we knew it, we did all we could to feel them in their fullest. In the so-called honeymoon phase we weren’t wasteful at all. We were completely dissociated and detached from any previous sense of reality and in that regard, we were in love.

Agnes had contagiously interesting theories on identity, particularly that one can’t really exist without the feeling of an opposite, an enemy. I don’t like this, I don’t like you, therefore I am. We would not be without the invisible enemy, is what she’d always say.

I would ask her:

‘So what do you hate?’

‘Well, for me it’s conservatives and for conservatives it’s me, but more personally speaking I don’t like that guy Jon Hughes in my program because I think he’s a bad journalist who believes he’s a good journalist and there’s nothing worse than someone who thinks he’s good at something he’s bad at. So I don’t like Jon and I don’t like conservatives, and I exist. But in reality, Jon and conservatives need to exist themselves for me to feel a presence.’

‘So do you believe that contempt leads to all of the strongest emotions that make us feel alive?’

‘Unfortunately. But I think it’s beyond just contempt leading to the superficial emotions. It’s not just hatred or knowing what you don’t like.’

‘Then what is it?’

‘I can’t say, I wish I could. I can sense an opposite, so I know I’m here. It’s not just the practical, the Conservatives and Jon Hughes, it’s also the invisible, the sense of something that’s different that makes me know I’m really here.’

‘The invisible enemy?’

‘Right, we’re all more or less fighting an invisible enemy, constantly, and it’s what makes us feel the most alive.’

Agnes was doing that thing we all do where she would flesh out her opinion more and more as she talked, perhaps an opinion she wasn’t even aware of before she brought it up, and then acted as if it had been her philosophical perspective for several years. Although, that could have just been a minor side-affect of being so intimate with someone, too aware of how my counterpart formulated her opinions, too aware in general. I did feel alive.

I came to the conclusion that Agnes was right. There were multiple forms of invisible enemies that confirmed who I was and rationalized my desires. The various ideas, structures, and even people who existed in my mind just to build an assurance in myself.

I even took it overboard, beginning to label my own apathy as an invisible enemy. The forces that caused me to not write and do my work; invisible enemy. The craving for sugar and fatty foods; invisible enemy. To get caught up in the past and not look to the future; invisible enemy. To write, to eat well, to have a healthy state of mind became the most vital aspects of my life because of the strong, self-destructive will that threatened its existence. These enemies had to be defeated, I must survive.

And survive, I did, survive we did. Night after night we would sleep together in bed, subconscious intertwined, dream together, nightmare together, a unit that stood strong against all the forces of the world. Yet, there was something inhibiting me from enjoying this pleasure to the fullest, a stark feeling that this would not last forever.

I decided to cherish every moment of falling in love while I still could, the fantastical purgatory between reality and devastation. Sharing your dreams and nightmares night after night is inspiring, formidable, pick your adjective, but it wasn’t like I didn’t have a feeling of longing for taking back control. I chose to let fate decide when.

Those conflicting emotions were awfully strange; indulging in the illusory perpetuity of love while simultaneously aware that sooner or later it would all end.

Two years passed like nothing at all. Friends were lost and gained yet Agnes and I stayed together. It isn’t to say we didn’t have our petty arguments, but we still loved each other, and the force we felt at the very beginning had been superglued to the foundation of our relationship. The fellowships were up and therefore our funding too. German newspapers weren’t really hiring and neither of us was able to secure contracted positions as foreign correspondents. We spent the last few weeks in bed together arguing over what would be the best thing to do and came to the conclusion that I would go back to New York and she to Edinburgh, and we would each apply for jobs and visas in each other’s cities. The first to be successful would move. If one of us got a job but not a visa it wouldn’t count and the same vice versa. If time took its course with no successful applications, and we gave in to disillusionment, then we would be letting our invisible enemies win us over. And if we were beaten by our invisible enemies than nothing would matter anyway because we wouldn’t feel alive or know that we existed. And to not have the awareness of being alive or the knowledge of one’s own existence was to accept the fact that we were already dead. Was death the greatest invisible enemy of them all?

14 months went by and I grew out my hair then got a hair cut and noticed my hairline had receded slightly. Agnes went from brunette to blonde, as one does. We slept with other people but didn’t bring it up, having a kind of unspoken agreement that some battles are worth losing if we want to win in the long run. No jobs in the UK for me, no jobs in the US for her. As time continued to pass we would practice our German more and more during our almost nightly Facetime sessions, utilizing all the free language apps available on the internet. We had come to the agreement that we were both fluent enough to be hired somewhere, anywhere in Berlin, and agreed to quit our current jobs and meet there in one month’s time.

New York and Edinburgh were bastions of a place that once was and had condemned themselves to nothing but conspicuous consumption, the free market, and neoliberalism. All the big western capitals were slowly becoming tributes to what they once represented, and it was important for both of us to return to the place that still felt authentic and lively. So, we did.

I went back in the middle of a cold February on a tourist visa that would eventually turn into an artist one. I found a job as a barman and they paid me enough under the table to live in a decently priced studio I had found online. Agnes got a job as an assistant audio editor for Der Spiegel’s podcast production. It wasn’t exactly journalism, but I suppose we all have to compromise to get where we want to go. Better together than apart, better happy than sad, we were ecstatic to be in the same city and place once again.

The city had a different tone than when we had first fallen in love, and so did our love itself. The connection between us wasn’t as harsh nor mystical, the novelty unavoidably disappeared, it was all more routine. When we would wake up in the mornings and make coffee and toast, we really were just making coffee and toast. Not everything had the sharp tinge of excitement it once had. But we remained resilient, taking it as a sign of things to come, a new chapter of life that could be seen as both joyful and mysterious, celebratory and uncertain. Not every phase is so straightforward, so many conflicting emotions are experienced at once.

One year became two and two became four, Agnes was promoted at work, and I became manager at the bar. Not only did I speak fluent German but also gained a pretty good hand of French and Spanish. I got heavier, not as slight as I was in my early 20s. All the nights spent sitting and drinking with colleagues after work had taken a toll on me. Agnes’s weight didn’t fluctuate as much as mine, except now she was gaining weight due to a welcome but unexpected pregnancy. And why not have it? Things were fruitful. Both of our salaries were good enough to move into a comfortable three room apartment. Agnes’s mother, Audrey, a 74-year-old widow from Aberdeen, had moved to a vacant apartment upstairs. Audrey was lonely in Scotland, feeling isolated as all her friends began to slip away like sand falling through one’s hand. Audrey needed a change, didn’t we all? We were happy to have her around. At first I thought it would be kind of annoying but it ended up being all right, it was nice having that kind of figure in my life, and Audrey and I got along and would go for walks and eat dinner together when Agnes was out of town. My parents passed away when I was so young that it was almost irregular if not bizarre to have Audrey to turn to. And she would make Haggis, which was repulsive, yet endearing. Audrey was excited to have a grandchild to look after. I couldn’t believe I would be having a child to call my own.

Agnes and I would sit in the kitchen late at night considering all sorts of names. I don’t know why but we both kind of assumed the child would inevitably be a girl. I had some feminine attributes and was incredibly sensitive, Agnes came from a family of women, it just made sense. Although, secretly, on my way to work or up in the middle of the night I would fantasize and hope that the child would be a boy, a son to call my own, how cool that would be. Maybe he would have an old school name too, like Douglas or Harold. Definitely not something German, like Albrecht or Timo.

Aside from a few freelance articles here and there I had for the most part given up on journalism altogether. I was writing stories, fiction, in my free time, and was getting published in a bunch of literary journals based in the US and the UK. As long as I was able to make a living at the bar, which was constantly populated and therefore profitable, I was happy not to have to economically rely on writing, to do it in the mornings or late at night when everyone else was asleep and I had the peace and quiet to sit and think and convert past experience into imaginary pleasure. And to not rely on it as my sole source of financial income had in a strange way made my work far more appealing. I was able to come up with sentences and rhythms I had never before thought I was capable of. That was what I wrote for, those strange feelings where somehow you produce sentences that come out of the blue, almost as if a cherub had softly placed them in the palm of my hands while the mind was at work constructing the outer lines of the narrative. I was happy, I was writing, I was living life comfortably without worry, and I had a child on the way. There was even a little bit of a following who would keep tabs on all of my published work, writing congratulatory fan mail, asking me to elaborate on certain characters and themes in future stories. I rarely listened to any of it, but it gave me the confidence to keep on going. What I remember most from that period of time was above all else the desire to write the way that silk felt.

I think it was a Tuesday afternoon, just before I had to get to the bar when I got an email from a well-known publishing agent asking me to come meet him in New York to discuss not only a short fiction collection, but perhaps a position as an editor that he had in mind for me. Why not come? He would reimburse the flight and provide a stipend for five days. Per diems, meetings, a couple literary events he said I must attend. This can’t be, was I dreaming? I thought the hay-day for literature had been over, I mean, really? Really, he said.

I had given Agnes a kiss on her belly before arriving at her cheek. We were standing on the street outside our apartment and it was a relatively warm day in the middle of March. I told her it would just be five days. Even though she had put up a fight for me to wait until after the baby was born, I could tell she was proud of me. She looked at me a little differently, like she was choosing to spend her life with not just a failed journalist who managed a bar and happened to be trustworthy and good in bed. There was now a glint in her eye that portrayed an excitement to be in love with a writer. Perhaps someone gifted with a bright future, a man who represented a life of fortuitous circumstance and exciting trajectory. Who knew what could lie ahead, who knew what could happen in just five days, how our lives could change.

Agnes was wearing these big red sunglasses that looked quite hip, like a pregnant clairvoyant who shopped at all the right places. I turned to walk to the train station and she pivoted her hips in the direction of our build- ing before I looked back and shouted:

‘Agnes!’

‘Yes?’

‘I’m not Red!’

‘What?’

‘I just, I’ll miss you so much while I’m away and will be thinking of you constantly. I just want you to know, since you’re wearing those glasses, that I’m not red!’

Agnes lifted her finger up to the top ridge of her sunglasses and lowered them slightly. She took one good look at me and smiled.

‘I see now. You’re right. You aren’t red at all.’

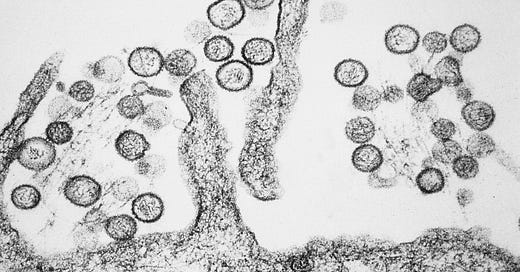

Upon landing, I received messages to let me know that my first two meetings had been ‘postponed indefinitely.’ Before having the chance to even be diagnosed, the elderly were dropping ill to an obscure, horribly contagious viral infection, many dying within a few days. These deaths stunned the world, so many in quick succession. It was like it all came from nowhere, a 2AM punch in the face from a stranger on the street. We had been warned, but no one gave it much attention until people started dying.

I remember calling Agnes on the way to my hotel, she was nervous but hadn’t yet known anyone personally who was infected. Her mother was fine. She felt decent, protected by family and a good community of friends nearby. Our upstairs neighbor, Christian, was around to help if they needed anything. I had agreed to come home earlier if my meetings kept getting canceled and the situation escalated. The closing of borders was unthinkable, if not absurd.

Sitting in my hotel room, I was as ignorant of the precarity in our ‘free will’ as anyone else was, but the speed in which the elderly and sick were dying was unprecedented. I should have known nothing would ever look the same, I should and could have acted quicker, but in retrospect, I’m oddly happy that I didn’t.

That night I ordered room service, a club sandwich with fries, a beer, and a strawberry milkshake. A valet wearing a protective mask and rubber gloves came up with the food. He wouldn’t accept a tip in cash, he didn’t want to hold it. I didn’t eat much and fell asleep watching the news on CNN. I dreamt of a brown Labrador Retriever that walked toward me slowly and cautiously in the middle of an expansive gray desert. The dog looked at me in the eyes, wearily, before sputtering his lips and walking away without confidence.

I woke up to a hysterical phone call from Agnes, I had slept until 11. She had called the room directly, my phone had died in the middle of the night. On the way to the grocery store, Audrey had dropped dead, like an anonymous fly in the middle of summer. Dead. Our building had been placed on lockdown. No one allowed in, no one allowed out. This was happening all over Berlin. I told her to stay put, that I would ask if Christian, our neighbor, was home to help out if she needed anything in the meantime. I would change my flights to the next one out. I called Christian and he said he felt fine, no temperature or fever, no symptoms. He would go down to our apartment and through the door, ask if Agnes needed anything. If she did, he would cover his face with a scarf and take care of any emergency. He would check in every few hours, no problem at all, he assured me.

Pacing on the street, it was when I got off the phone with Christian that I overheard someone outside my hotel say that the American borders were being shut, effective midnight. I almost laughed in disbelief before entering the lobby, only to look up at the TV screen by the bar to have the dismal information confirmed. They were letting in European citizens and permanent residents for the next 24 hours but technically, I was neither. A front desk agent informed me that the hotel was shutting down operations within the next 48 hours and that I better find somewhere new to shelter, quarantine laws were likely.

I booked the next flight out and got a cab to the airport. There were no cars on the street, traffic had never been so light. The driver was telling me a story about his son and I remember not being able to listen, just rotating my gaze between the window and my cell-phone, anxiously shaking my leg.

I walked briskly toward the gate before being denied a boarding pass and being instructed to go home. I didn’t have the right visa, they couldn’t let me on the plane. I called Agnes and she started crying, I did too, promising I’d do whatever I could to make sure they’d allow me back into Germany as soon as possible.

My best friend from childhood was the heir to a logistics empire, his father had founded what was to become one of America’s largest networks of the country’s global supply. He had found himself trapped in Monteverde, Costa Rica on a work trip, managing something to do with coffee beans. Or maybe it was cacao beans. I can’t quite remember. However frustrating I always found social media, I wouldn’t have known exactly who to call when looking for a place to stay if it were not for a tweet he wrote detailing that he was stuck in Central America, trapped but doing fine.

He was balancing 1000 things, he told me, and like everyone else, didn’t have much time. I explained my situation quickly. He sounded unaffected, as if I told him some banal news about what I had eaten for dinner the prior night. He said to go to his apartment in the Flatiron district, he would write the doorman to hand me a spare set of keys.

‘Thank you,’ I had responded.

‘It’s not a problem,’ he said. ‘Logistics is an unpredictable business, I’m used to spontaneity, as prepared for this as anyone else.’

He confidently added that, ‘in a situation like this the American supply-chain would remain intact, you might go crazy, you might lose everything, but at least you won’t starve.’ Before saying, ‘good luck, and try to water the plants until I get back.’

I felt then for the first time that this was likely to be a while.

The apartment was expensively furnished and surprisingly bare, with nothing on the walls, a few sill plants, scattered family photos, altogether culminating in a spiritually antiseptic atmosphere, all so very typical of a young businessman’s abode. At least it felt clean. I wondered how strange it was that stereotypes can still be accurate, how people still happen to correspond with the colleagues in their profession, an invisible social code that everybody, including my friend, had taken home with them. There were a beleaguered pair of black leather boxing gloves hanging above his desk.

I spent the next several hours on the phone with airlines, seeing if I could make a way out, all the while in constant dialogue with both Christian and Agnes, getting minute by minute updates via text message of how Agnes was feeling, as well as any plans for Audrey’s funeral. I had hoped to at least be back sometime in the next several weeks. I acquiesced that I wouldn’t be getting back immediately, but with the death toll of this mysterious virus rising ever so steadily, there was now the stark likelihood that I would not be present when Agnes went into labor, never mind any mourning for the death of her mother. Would all this panic and worry prevent the child from being born at all? My whole life I had said powerless this, powerless that, throwing around adjectives like they were to be taken for granted, but never before had I felt the word in its most consummate form.

When all the world leaders began to wage war against an invisible enemy, I couldn’t help but think that humanity had for once found a common identity. It wasn’t the time to bring this up to Agnes. I would also be lying if I didn’t admit that, within the depths of my consciousness, there wasn’t a feeling of peace and relaxation that embodied this crisis, a crisis that fell in the most important time of my life. A stillness passed through me that I had never felt before, and it was oddly comforting. Feelings don’t lie. This same sense of calm passed through New York City, a steady wind of serenity amidst ravaging chaos and worry. The economy crashed and people were dying left and right while scrambling to structure a hopeful future. The inevitability of crisis, of an unstoppable societal downfall, was what caused in me, and I suspect in many others, a bizarrely peaceful sense of equanimity. Everyone is equal in the grave. I would always feel that while walking on to an airplane passed all the passengers in first class. If this plane goes down, we’re all fucked. It was the same sort of feeling when the virus broke out.

Most international flights were canceled, world leaders got infected and many became hospitalized and some even died. People stayed home and watched TV and panicked and connected on the internet, which wasn’t too different from what was going on before. To curb the risk of infection, most people stopped going to stores and ordered in most supplies. There were reports of delivery staff in the service industry getting the virus at a higher rate than anyone else. More panic ensued. The bottom of capitalism’s caste system whom the rich parasitically relied on were becoming too sick to serve. This really worried people.

Our building in Prenzlauer Berg was still on lockdown. It became clearer and clearer to everyone involved that there would be no funeral any time soon for Agnes’s mother. Worse, it was now clear that there was no way I could be around when Agnes was scheduled to go into labor. We had to make a plan of who would be there for her, and how.

‘It is no bother,’ Christian, pronounced Krist-E-Yan, said. ‘You think I have something more important to do?’

Christian didn’t have any immediate family in Berlin. His father was in Bavaria and his mother in Warsaw, they had been divorced since he was young. He was an only child, like me. He said his parents were on ‘put in your area and stay,’ like everyone else’s, and if they were infected there wasn’t really much he could do anyway. Everyone was immobile.

‘Agnes health is top priority, it is all I can do right now to help the world and I am happy to. I have your back-side.’

Christian was in his early 40s with thick blonde hair and relatively handsome, symmetrical features, a little overweight with a red nose from drinking slightly too much for a touch too long. I remember him carrying the warmth of someone from a small town, a warmth that was infectious even after a small conversation. His eyes were always ingratiating and juxtaposed interestingly with his Slavic demeanor and gait. As helpless as I found myself, there was an incredible amount of solace in Christian’s existence. Forces beyond my control were slowly beginning to absolve me of the duties of fatherhood, at least for the time being. I felt both uneasy and relieved.

Around three weeks later, a nurse in a hazmat arrived at Agnes’s door in the middle of the night to deliver a baby. Christian let her in, and if my memory serves me right, he held Agnes’s hand for the duration of the process before cutting the umbilical cord. A boy was born and we named him Oliver. Christian agreed that it was a nice name for a boy who would become a gentleman, the right name, in fact.

‘Wave to daddy,’ Christian said, pointing the camera toward Oliver, while Oliver just stared blankly back at Christian.

In the back of the frame I could see a nurse that looked like an astronaut wiping blood and sweat off of Agnes’s body, sprawled out on a makeshift hospital bed in the center of our living room. Through the process, my video connection repeatedly cut out, and the last time that it broke I couldn’t get reconnected and ended up going to bed and dreaming of a meadow without any flowers. I heard a voice that kept saying, ‘Here! Here! Come here!’ But I didn’t know what here was nor where the voice was coming from, then the imagery drifted to nothingness, and I woke up with a hard-on and began the day.

I found a job writing copy for a mobile ad agency. I was referred by the publishing agent who had gotten me into this position in the first place. There was a surprisingly large range of work for writers, a variety of organizations needed clean, articulate press releases to keep the public informed. People were sick and dying, including the unfortunate that used to have those jobs. Within two months I had a wealth of work, and they paid directly to my account with 10% going to the agent. He too was doing what was needed in order to survive.

One month became three months, and three became six. I was able to order whatever I needed online, including protective gear of my own so that I could go out to take walks and buy groceries from the few stores that were required to remain open. My friend was still trapped in Monteverde. He had rented a house with a pool and had been working from home, managing shipments of critical supplies all around the world. The infections there weren’t as bad as New York City, and he was able to take daily walks in the tropical forest. He told me that business had never been better, he had never felt healthier, there were worse places to be trapped.

There were the daily conversations with Agnes and Oliver, and by then Christian’s presence around the apartment had become ubiquitous. I slowly began to feel more and more removed. I didn’t want to feel removed, but I couldn’t help it. I still felt love for Agnes, but it was almost like she had never been pregnant in the first place, that Oliver was completely disassociated from me. Agnes felt this distance, even over the phone. She never brought it up, just asked how I was doing, how I was coping with being alone. She was always generous in that way.

‘Fine,’ I would routinely respond, not giving up any more information. Something in me sensed emotional boundaries had begun to become necessary. The more intimate I let myself be with her and Oliver, the greater the heartbreak that might ensue. Fine, I’m doing fine. I’m eating. I miss you. I love you. We’ll be together soon when everything’s sured up.

I sent 75% of my income to Agnes’s account every month, I only really needed 25% of it, and even that was enough to keep some savings. My friend in Monteverde owned the apartment, he refused to accept any rent. My expenses were food and utilities, zero to none. I would be lying as well if I said that I didn’t find a sense of comfort in the simplicity of the structure I found myself in.

By Oliver’s first birthday, one-third of the global population had been infected, the death toll 35%. For measures of posterity, the victims’ names began to be published on an online database. I assumed this was for the ornamental memorials by then inevitably on their way, monuments and cenotaphs that would end up spanning the world. Suva, located in Fiji, remained the only municipality with a zero infection rate.

The mandatory quarantines didn’t seem likely to go anywhere any time soon, people kept on dying, the size of the unplanned memorials remained ever-expanding. A vaccine was being developed, was hopefully on the way, though the timeline still hopelessly unclear. Christian and I maintained a steady dialogue, and by then I was almost certain he was sleeping with Agnes. I was happy she wasn’t alone, comforted that Oliver would have a father. I remember masturbating one evening to the image of Agnes and Christian together in my bed.

As for my paternal duties, I suppose the best way I could describe it would be like a soldier discharged, not honorably or dishonorably, but only due to the most particular matter of coincidental circumstance.

And yet we continued to have our online correspondence.

As time went by, like a train with no destination, one year turned into three, and I noticed from photos that Oliver looked quite like me, my eyes and my ears in particular. I remained emotionally remote, merely a helpful presence.

I felt love for Agnes, but was no longer in love. She was a person that existed far away, like a friend I once had but unfortunately lost touch with. I eventually took down the photograph I had printed out of her and Oliver. I didn’t like looking at it. It was like a symbol of an unhelpful past, and everything that belonged to it had ceased to exist, at least emotionally. My memories were visible but ungraspable, no longer there to be lived in.

As long as I kept sending money, contributing in some way, I felt OK to keep living my life with a minimum of presence within theirs. Christian and Agnes now shared a bedroom. Christian had built Oliver a crib made out of wood, Oliver would be raised in a world where going out in a hazmat suit was as normal as drinking water. His first word was Mommy and I think that shelter and quarantine were both in the top 10, although that’s probably me just projecting.

I had stopped writing almost entirely. My friend in Monteverde had called me one afternoon saying that his team was horribly understaffed, they needed someone to book shipments, to help out with operations. The job was simple, menial and administrative yet considerably profitable. He suggested I would pick it all up within a few weeks and that whatever money I was making writing copy he would personally double, I was to become a businessman, my fate would once again never cease to surprise me. And the way things were going, why not. I was able to send more money back to Agnes and Oliver, though at some point in the middle of year three Christian began saying that the amount I was sending was unnecessary, he had enough to cover the essentials. There were hardly any expenses anyway. I didn’t listen, although thinking back on it now I really should have.

Until the end of the plague, I had the same schedule every day. I would wake up at 11 AM, put on my hazmat and take a stroll as far as I could until I got tired or a member of the national guard gave an empty threat to detain me if I didn't go home. I enjoyed walking along the deserted Hudson river, where there was no longer anything to see except docked hospital ships that were so long as to appear to touch the very repugnant shore of northern Jersey. The streets of New York were empty and eerie, like one of those movies where a great apocalypse has hit. Most peculiar was how after the physical presence of New Yorkers had vanished, incorporeal personalities still appeared to roam the streets. Something was going on, I just couldn’t see it. I imagined ghosts of New York’s past walking the streets saying how they could breathe again, before becoming exhausted and going back to their ghostly homes, both large and small.

I would usually get back to the apartment at around 2 or 3 PM, eat something like oatmeal or toast, before sitting down and starting work. The job was simple, to manage cargo across ports between the Americas. Cargo of critical supplies and occasional luxury goods like caviar and South American natural wines that were continuously bio-engineered at farms indoors. Tax-rates were adjusted and very little negotiation was ever necessary. My friend was right, our supply chain was exceptionally sophisticated.

Though one would think sweatpants would be the new normal, I still got dressed every day, shaved my face, and took good care of myself. Slacks and button-downs never became obsolete. I even sprayed splashes of my friend’s cologne. These things were important for restoring my humanity. If I had let myself go, who knows what could have happened. There were a few situations where I considered autoerotic asphyxiation, but never had the guts to do it.

Routinely, work finished around 10 PM and it was then that I liked to start drinking, single malt or red wine, rarely anything else, opening my tablet and reading something classic like Tolstoy, Wilde, Austen or Cervantes before passing out at around 4 AM. It was always incredible to me how the constructs of time still held in place. Other than sex, I didn’t really miss human contact, it would have actually been quite uncomfortable to have to look someone in the eye and talk to them in person. Phone calls, no, email, was actually preferable.

There was a tastelessly gigantic screen in the living room. I moved through the decades of film history rather gracefully and found myself in love with new auteurs, Kar-Wai, Pasolini, Varda, and out of love with previous favorites, Fassbinder, Truffaut, Hitchcock. Life’s pleasures were confined to wine, scotch, literature, and cinema. I never had one economic worry. True, the lack of sex and erotic touch was still a problem, but everything else was actually quite decadent. In a sad way, I was truly one of the luckier ones. Aside from the possible rare enchantment, I began to think that life spent alone with Agnes and Oliver would have probably become frustratingly depressing. I was happy not to have to encounter those range of emotions.

I would sit and jot down notes now and then, but it was different from before, it didn’t feel the same. I had used to define myself as a writer by being different from the common denominator that moved through society, an anomaly with a unique perspective. Now I felt lucky and privileged. I couldn’t write about Oliver because I didn’t know Oliver, and no matter how much I tried I just couldn’t get myself to genuinely care about or feel love for him, never mind imagining a reality for him that didn’t exist. The journals that I kept, the writing I ended up doing, were mainly descriptors of the elaborate meals I would cook once or twice a week.

I occasionally stopped to ponder how this is what existence had become, how bizarre, what the fuck. Sometimes drunk, I looked into the mirror for a while, here one minute, still there the next. Sartre would have wagged his finger in my face and said I told you so. Pestilence changed my life forever, the course not stopping where it once seemed it would. How to make God laugh? Tell him your plans.

Five years appeared since the beginning of the pandemic, a promising vaccine finally arrived. It took me five months to actually be vaccinated and would take the remaining population, 65% of what was, another 18 months to be taken care of. Even the ultra-religious and supreme anti-vaxxers were now in agreement to do whatever it might take. It’s funny how circumstance causes the most ostensibly fundamental to show their cards.

It was almost exactly seven years since I had left that I was allowed to return. I was born on July the seventh, and I guess it’s always been my lucky number. Agnes and Christian knew I was coming, and they were nervous, it was unclear how we’d all move forward. I wasn’t exactly clear myself as to why I had booked the trip, but it felt necessary to go, no matter how many times both Agnes and Christian asked me if we could wait a little while. I had to feel the situation out first-hand, I had to see my child and know for certain how I really felt. The idea of closure seemed necessary.

Apparently, Oliver, and most born in his generation, refused to go outside without their ‘space suits,’ stubborn in their beliefs like old people who refuse to accept a changing world. Walking outside and smelling what could be smelled for the first time at the age of six was really freaking Oliver out, an attack on the senses. He would need to be in therapy but apparently there was no therapist who quite knew how to deal with these particular traumas. In that case, psychotherapy was deemed better than developmental, though, in practice, medical professionals seemed to be teaching themselves from scratch, everyone was learning as they went.

There was another issue; Oliver didn’t know who I was. He was raised to believe his father was a Polish-German named Christian, not a Jewish man from New York. I was the friend they would talk on the phone with. The plan was for me to meet him, but the role I would play in his life was yet to be determined.

When I rang the bell to the apartment that used to be mine my heart didn’t race but maintained a steady pace, it was almost as if deep down I already knew what was going to happen.

Christian met me at the foot of the building. He didn’t give me a hug so much as a chest bump, physical interactions with strangers were still very awkward. It was OK to touch but it still felt like it wasn’t.

‘Why don’t we go for walk,’ Christian said, not asking how I was, not even really saying hello. There was a coldness to him and I could tell he was doing his best to hide the natural ingratiation that his eyes used to always reveal.

Walking through Mauerpark, we each put on sunglasses and bought coffee from a stand that recently resumed operations. Christian broke the news, I understood. Oliver was dealing with enough, we were all adjusting to a new life, a new world. This was the last thing he needed. Maybe one day, down the line, but for now, it would be best if I weren’t involved, if I stayed away.

‘You’re not as emotional as I thought you’d be,’ Christian remarked.

‘I guess we never really knew each other.’

‘No, none of us did.' So you’re a cold bastard then?’

Christian chuckled and I didn’t, though personally, I was happy to see him show face.

Every step we took felt harsh and masochistic, I couldn’t wait for the walk to end. We circled for another 20 minutes or so and got back to the foot of my old apartment. I looked down at Christian’s feet and noticed he was wearing an old pair of my socks. Christian noticed I noticed and got uncomfortable. It went without saying that Agnes didn’t want to see me. Or no, not didn’t want, but couldn’t allow herself. Agnes and my son were a few meters upstairs, so close, but so fucking far. This time Christian and I hugged.

‘We do what we can for each other,’ he said to me with European sincerity.

‘Do we?’ I thought to myself, before nodding and walking away.

When I got back to my hotel I felt a rush of pain in my head so acute that I convinced myself I would die of an aneurysm, a symmetrical tragedy might have to take place where I would need to die for Christian to really have Oliver as a son. I must die.

I returned to the apartment later that evening and this time Agnes came down first. Seeing her was surreal. In the photos I couldn’t tell, but her face seemed different, the only thing recognizable were her eyes. My heart began to beat very quickly and we looked at each other for round 20 seconds before hugging, a long, protracted hug, the most intimacy I had received in quite some time.

‘I’m sorry,’ I kept saying. ‘I’m sorry. I shouldn’t have left. I should have stayed, I should have waited, I’m so sorry.’

Agnes remained quiet and held on to me for a little longer, before saying I could come upstairs for a few minutes to say hello, but that Oliver wasn’t doing well, it would be better to wait until society gets back to normal before trying to build a real relationship with him. Any immediate truth about who his father was would remain out of the question.

Oliver’s hair looked blonder than mine, it was the first sight I caught of him, sitting at a desk facing the wall. He was in the middle of building some sort of puzzle that looked like zebras and lions walking around a city. There were toys strewn around the apartment and it was pretty messy, loose flower on the kitchen floor suggesting that someone had been baking. All the artwork on the walls remained the same as before I left. Christian was sitting next to Oliver, helping him work on the puzzle of a city inhabited by Safari creatures.

‘Oliver, our friend from New York City is here to say hello,’ Agnes said.

‘Wass?’ Oliver answered in German, with a German accent. I shuddered a little bit.

Agnes repeated the same thing in German and he came walking over, wearing a face- mask that he was afraid to take off.

‘Hallo,’ he said to me with a smile. I froze up and stared at him blankly for a little too long and I think he got weirded out, because he just ran back toward Christian to continue working on the puzzle. It was very awkward in the room, they didn’t want me there, and even though it was my furniture, it didn’t feel like my home. Nothing in there felt like mine.

I sat in the kitchen with Agnes and caught her up on the work I had been doing and the time I spent in isolation. She further informed me on some of Oliver’s developmental troubles due to the Pandemic, before Christian came in and said it was time to put Oliver to bed. He had sleep issues, apparently, and there was a whole process they had to do before bedtime. I didn’t ask too many questions, just nodded understandingly at the consequences of an entire life spent indoors. It was clear I already stayed a few minutes longer than Agnes had wanted me to, and on my way out I went over to Oliver, still at the desk, and asked what he was working on. He looked at me with my eyes and smiled.

‘It’s the invasion of Paris,’ he said in a German accent, with a lisp. On close inspection I could see the Eiffel Tower in the background of the puzzle. ‘The animals enjoy it more than the forests because the food is better. And the elephant, the one I’m making now, he likes the food the best. All the people are scared so they stay inside.’

I was about to give him a hug, before realizing that he might find it creepy, if not weird. There was an impulse in my mind to say something stupid, like — you know I’m you father and we got separated because of the... but I didn’t. I do wish I could have hugged him though, it would have felt nice.

When Agnes walked me out I asked her how it came about that Oliver ended up having a German accent.

‘From the TV,’ Agnes responded. ‘Christian likes to watch a lot of domestic crime dramas.’

From the tone of Agnes’s voice I sensed that the couple had problems of their own, a whole world I had nothing to do with. They were the nuclear family, I was just a contracted engineer, no longer useful or needed.

When I turned my back to walk down the stairs Agnes called for me once more, before beginning:

‘I know you’re not still in love with me, and I’m not in love with you. But I do still feel love for you, and I care that you’re doing well. We have a lot to sort out, but we’ll be in touch.’

I nodded, she shut the door, and I haven’t seen her since.

That night I went back to the bar I used to manage to find that it had shut down permanently. I knew this, I just wanted to see it first hand. It was a melancholy that I craved. I went to another bar around the block and drank beer and schnapps for several hours. I met a flight attendant named Berthe who had just began work again, she was on her way to Paris in the morning.

‘I prefer the food there,’ I remember Berthe saying.

After drinking cognac we went back to her hotel which was an IBIS budget near the airport. Her room was messy and smelled like stale pastries and drug-store perfume. We had pretty decent, aggressive sex for several hours. She was the first person in seven years, the first new person in over a decade. She put a finger in my butt, I fucked her in the ass. She squirted and I came on her face, which she scooped up and then put into her mouth. This made me hard once more and then we fucked, not made love, again. It was dirty and I enjoyed it. We did all the things to each other that we had watched on the computer for so many years. Berthe fell asleep and I went to the shower, before sneaking out of her room to go back to my hotel to sleep alone. There was no way I could sleep in the same bed as anybody else, I wasn’t use to it.

On the plane back to New York, I wept for several hours, routinely slamming my fists on the tray-table in front of me. Normally, people would have consoled me, but everyone assumed everybody else had been through similar tragedies. There was no point in consolation. In the collective consciousness of a doomed reality we were all dealing with our losses together. Just a subtle nod was consoling enough to say, ‘I understand your pain.’

Leaving Germany felt right, there really was nothing there left for me, at least not for now. Maybe one day, maybe down the line. Life would start again.

There’s that feeling of looking in the mirror after a long period of time, a time without self-recognition when one feels as though they’ve lost their bearings. Who have I become, what am I, what the fuck is going on? But then you look into the mirror, right into your own eyes, and you see yourself, and say, ‘oh, there you are,’ and everything seems to be slightly OK again.

And here I am. I continue to work in logistics and try to remain positive. New York is different now, a cross between the romanticized 1970s and a technological utopian future, the present existing between both forces. I’m writing my story to articulate my past to the best of my ability, to try and summarize what I’ve been through. The process has been difficult, and I can’t help but wish things were easier to see immediately instead of in retrospect.

Experiencing what I experienced has caused me to have a particular perspective of subtle indifference. I am open to any event and closed to many connections, that paradox now defines me. I suspect that many others have had similar sentiments, and have run into even odder circumstances, all culminating in a series of secret sensations that everyone shares, the personal feelings that are collectively experienced, like sitting in a crowded movie theater.

When I am done with this section of my life’s story, I will print it out and delete the file. Once printed, I will reread it once, before setting fire to the physical manuscript. The words will evaporate into the air and turn into smoke before becoming invisible, just a smell that will eventually disappear, an existing force that I will avoid. An invisible enemy, one could say.

Right after the virus broke out, everything had such a bizarre finality to it. The last meal, the last shave, the last shit, the last time you could say I love you. But life persisted, things moved on and in remote proximity events took place. Like always, people fell in and out of love, out of routine, out of phases, before somehow finding a way to move on. Children were born and parents died. Some children passed before their parents even had a chance to, and through it all, it was hard to tell which direction to look, and it happened to be that the only answer was, and is, forward. God is right in front of us. And tomorrow will exist, with every new day different from the last.